Wheat

History of Wheat

Wheat has been important to Oregon since the days of the fur traders. Dr. John McLoughlin required each Hudson Bay trading post to grow enough wheat to feed the people of the post and the people served by the post. Dr. McLoughlin traded wheat for Russian furs and that opened the export market for Oregon Wheat. Wheat also came to the Oregon Territory with the big wave of settlers in the 1880’s. The people who came to the Northwest carried wheat with them, wheat to eat and wheat to plant.

The first flourmill in Eastern Oregon was located in John Day in 1865. It was built to sell flour to gold miners. Today, the largest flourmill on the Columbia Plateau is in Pendleton. But, in the 1880’s most of Oregon’s wheat was grown in Willamette Valley. Shipping wheat to Portland from Eastern Oregon by riverboat or wagon cost the farmer too much. In 1883 the Union Pacific Railroad opened a line from the east to west across Oregon. The new railroad made it affordable to ship wheat to Portland. In the 1950’s, hydroelectric dams were built on the Columbia River. With the dams came locks that allowed easy movement up and down river. Barge companies were established to move large quantities of grain to the Port of Portland docks. With this transportation system in place, Eastern Oregon farmers were able to move their wheat quickly and affordably and became the leaders in wheat production.

Wheat fields in Eastern Oregon

Photo source: The Oregonian

Basic Classes of Wheat

Wheat is the principal U.S. cereal grain for export and domestic consumption. In terms of value, wheat is the fourth leading U.S. field crop and one of the leading export crop.

Wheat has two distinct growing seasons. Winter wheat, which normally accounts for 70 to 80 percent of U.S. production, is sown in the fall and harvested in the spring or summer; spring wheat is planted in the spring and harvested in late summer or early fall.

There are several hundred varieties of wheat produced in the United States, all of which fall into one of six recognized classes. Where each class of wheat is grown depends largely upon rainfall, temperature, soil conditions and tradition. Generally speaking, wheat is more often grown in arid regions where soil quality is poor.

Wheat classes are determined not only by the time of year they are planted and harvested, but also by their hardness, color and the shape of their kernels. Each class of wheat has its own similar family characteristics, especially as related to milling and baking or other food use.

Planting and Harvesting Wheat

Once the land is prepared, the seeds are sown in the furrows created by the raking or use of the wheat drill. When sowing by hand, a simple half circular movement with the wrist will spread the seeds properly. For larger areas, attaching a wheat drill to the tractor will allow the wheat seeds to be spread evenly and in place. Once the seeds are in place, make sure the area is watered properly. Wheat crops will absorb a large amount of water in a short period of time, so be sure to soak the area thoroughly. However, refrain from watering the area to the point that water is left standing.

Wheat being planted

When planting a summer wheat crop, be sure to water the area at least two or three times during the hottest months. This will provide the moisture needed to help the wheat crop grow properly. For a winter crop, there is a good chance that watering during the season will not be necessary. Test the ground from time to time to ensure that the moisture content remains within acceptable levels.

In all seasons, the use of some sort of insecticide will be a must. The exact type will depend on the season and the type of infestation that is native to the area. County agents can provide details on both commercial and natural insecticides that will work well in a given location and climate.

The final step in growing wheat is harvesting. Once the wheat stems, the time for harvesting has arrived. Using a scythe to manually harvest the wheat kernels is the time-honored process. For large wheat crops, the use of a combine machine allows for quick and easy harvesting of acres of wheat in a short period of time. After harvesting the wheat, the process of separating any chaff prepares the end product for grinding into flour or other applications.

A combine and truck harvesting wheat

Wheat is measured in bushels and a bushel of wheat weighs approximately 60 pounds. The wheat is weighed after it has been removed from the seed head. Only kernels are weighed, not the whole plant. Additional bushels harvested, means additional grain the farmer can sell to the local flour mill or elevator operator for shipment to Portland for export to overseas millers and bakers.

Inspecting Wheat

A sample of wheat is taken from every truck before it is unloaded into the grain elevator. The inspector examines the wheat for protein level, color, shrunken or broken kernels and foreign material in the sample. The grain is then sorted by protein level, moisture content and cleanliness they want in their wheat order. Some customers purchase specific varieties of wheat and are willing to pay more to have just that variety in their order. With all the testing and sorting that is done, the buyers of Oregon wheat can be sure they are getting exactly the quality of wheat they need for their millers and bakers.

Wheat Storage

Storing wheat has always been a challenge to farmers. On the farm storage bins, or silos, are made of steel and concrete. Many farmers have built grain storage bins on their property so they can separate different varieties of grain and market their crop when the price is right. The silo’s main function is to keep out moisture, insects, rodents, and birds. The silos are always completely cleaned before grain is stored in them.

One of the biggest enemies of stored grain is moisture. Moisture brings insects and mold. If the moisture in the grain is too high the quality of the wheat is lowered and it may be rejected for milling and baking. When this happens it is sold for a much lower price to be fed to livestock.

A grain silo

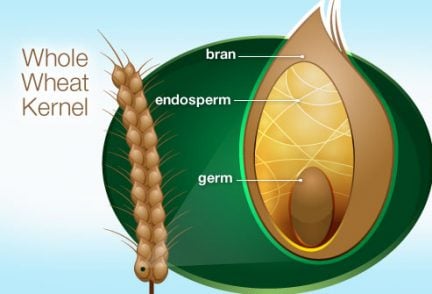

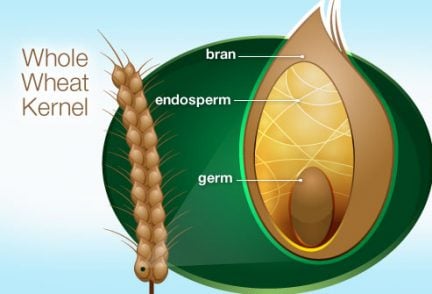

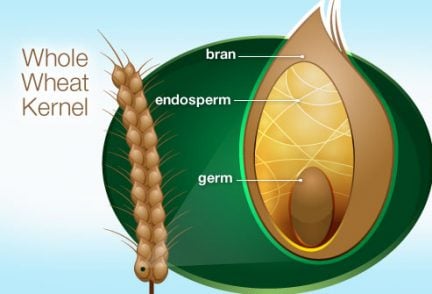

The Wheat Kernel

Endosperm

Endosperm is about 83% of the kernel weight. It is the source of white flour. The endosperm contains the greatest share of the protein in the whole kernel, carbohydrates, iron as well as many B-complex vitamins, such as riboflavin, niacin, and thiamine.

Bran

Bran is about 14% of the kernel weight. Bran is included in whole wheat flour and is also available separately. Of the nutrients in whole wheat, the bran contains a small amount of protein, larger quantities of the B-complex vitamins listed above, trace minerals, fiber.

Wheat Germ

Germ is about 2% of the kernel weight. The germ is the embryo or sprouting section of the seed, usually separated because of the fat that limits the keeping quality of flour. Of the nutrients in whole wheat, the germ contains minimal quantities of protein, but a greater share of B-complex vitamins and trace minerals. Wheat germ can be purchased separately and is included in whole wheat flour.

Types of Flours

All-Purpose Flour

All-purpose flour is the finely ground endosperm of the wheat kernel separated from the bran and germ during the milling process. All-purpose flour is made from hard wheats or a combination of soft and hard wheat from which the home baker can make a complete range of satisfactory baked products such as yeast breads, cakes, cookies, pastries and noodles.

Enriched All-Purpose Flour has iron and B-vitamins added in amounts equal to or exceeding that of whole wheat flour.

Bleached Enriched All-Purpose Flour is treated with chlorine to mature the flour, condition the gluten and improve the baking quality. The chlorine evaporates and does not destroy the nutrients but does reduce the risk of spoilage or contamination.

Unbleached Enriched All-Purpose Flour is bleached by oxygen in the air during an aging process and is off-white in color. Nutritionally, bleached and unbleached flour are the same.

Bread Flour

Bread flour, from the endosperm of the wheat kernel, is milled primarily for commercial bakers but is also available at retail outlets. Although similar to all-purpose flour, it has a greater gluten strength and generally is used for yeast breads.

Self-Rising Flour

Self-rising flour is an all-purpose flour with salt and leavening added. One cup of self-rising flour contains 1 1/2 teaspoons baking powder and 1/2 teaspoon salt. Self-rising flour can be substituted for all-purpose flour in a recipe by reducing salt and baking powder according to those proportions.

Whole Wheat Flour

Whole wheat flour is a course-textured flour ground from the entire wheat kernel and thus contains the bran, germ and endosperm. The presence of bran reduces gluten development. Baked products made from whole wheat flour tend to be heavier and denser than those made from white flour.

Other Flours

Cake Flour is milled from soft wheat. Especially suitable for cakes, cookies, crackers and pastries. Low in protein and gluten.

Pastry Flour is milled from a soft, low gluten wheat. Comparable in protein but lower in starch than cake flour.

Gluten Flour is used by bakers in combination with flours having a low protein content because it improves the baking quality and produces gluten bread of high protein content.

Semolina is coarsely ground endosperm of durum wheat. High in protein. Used in high quality pasta products.

Durum Flour is a by-product of semolina production. Used to make commercial U.S. noodles.

Farina is from coarsely ground endosperm of hard wheats. Prime ingredient in many U.S. breakfast cereals. Also used in the production of inexpensive pasta.

Nutrition

The USDA recommendations for daily grain intake depends on your age, gender, and physical activity level. They also recommend that at least half of your grains should be whole grains. Go to this website for more nutrition information.

Vocabulary Terms

Bran

the hard outer layer of the wheat kernel

Bushel

how the wheat is packaged after harvesting, typically weighing 60 pounds

Chaff

the part of the wheat plant that is separated from the wheat kernel

Combine

a machine that is used for harvesting wheat

Endosperm

the part of the wheat kernel that is ground up to make white flour

Scythe

a traditional tool used to harvest wheat

Silo

a storage bin for grains typically made out of concrete and steel

Spring wheat

wheat planted in the spring and harvested in the late summer and early fall

Wheat germ

the part of the wheat kernel that supplies food to the next generation of wheat plants

Wheat Kernel

the seed from which the wheat plant grows; it contains the endosperm, bran and wheat germ

Whole grains

foods that are whole grain contain the endosperm, bran and germ

Winter wheat

wheat planted in the fall and harvested in the spring and summer